We all love learning fun facts don’t we, especially if they’re something new and surprising. This animal can do something remarkable, this famous person has an unexpected talent, turns out you’ve been using this common kitchen item wrong your entire life you great walnut, bell peppers have genders and you can tell them apart by counting the bumps on the bottom…wait, what?

I spotted the image above on Facebook this morning. There is no source given for the information in the picture, and even Snopes doesn’t seem to know where it originated, but needless to say there is no truth in the idea that you can tell a male pepper from a female one by counting its lobes, and even if peppers could be male or female they wouldn’t have a gender. To explain why I need to take a brief diversion to visit the definitions of gender and biological sex before looking at what a pepper actually is.

Biologically speaking, sex is the production of offspring by combining the genetic material from two different organisms. The genetic complement of the offspring will differ from both parents. This is distinct from asexual reproduction, where offspring bud or split off from a parent to which they are genetically identical, as happens for example when plants grow from offsets or cuttings. While asexual reproduction does allow organisms to multiply rapidly, sexual reproduction has evolved as a useful technique to introduce genetic diversity into a population and hence potentially allow the offspring to tolerate conditions the parents cannot.

Sexual reproduction gets a little more complicated than just combining the genetic material of two parents though: if this happened the offspring would have twice as much genetic material as the parents, and then their offspring would have twice as much again, and then their offspring would have eight times as much material as the first generation… Another step is needed to keep the amount of DNA the same between generations. This is usually done by the production of specialised cells called gametes, which contain half of the parent organism’s DNA. When a gamete fuses with another gamete, a cell with the full DNA complement is produced which can go on to form an offspring.

Once a species has started reproducing sexually by means of gametes, things can start to get really interesting. If all individuals in the species produce the same sort of gametes, so that any gamete can fuse with any other gamete, the situation is known as isogamy. This immediately runs up against the problem that sexual reproduction arose to prevent – two gametes from the same organism could potentially fuse with each other, so no genetic diversity would be introduced into the next generation, and fungi in particular have come up with a number of fascinating strategies to overcome this issue. But another strategy to ensure that an individual’s gametes can only fuse with the gametes of a different individual is to make the gametes different, and only allow fertilisation to occur between gametes of the different types. This is where we encounter anisogamy or biological sex.

Once a species has divided its gametes into two types, it can specialise them for different reproductive strategies. Generally speaking evolution goes with a large gamete, which contains lots of resources (sugars and proteins and fats) to fuel the offspring’s growth and as a consequence can only be produced in small numbers, and a large number of relatively cheap-to-produce smaller gametes that can be widely dispersed in the hope of encountering a large gamete with which to fuse. We call the different types of gamete producers “biological sexes”, and call the large ones “female” and the small ones “male”.

The part that gets confusing for us humans is that, under all circumstances except when trying to make a baby, biological sex is functionally irrelevant to the way we interact with one another. No one ever felt a sense of pride in or solidarity with someone else’s achievements because they had the same size of gametes. No one was ever passed over for a promotion because their gametes were too big, or wrote that they were hoping to meet someone with small gametes on their dating profile. You can’t tell what kind of gametes someone produces just by looking at them and, until you’ve actually reproduced, you probably don’t know yourself.

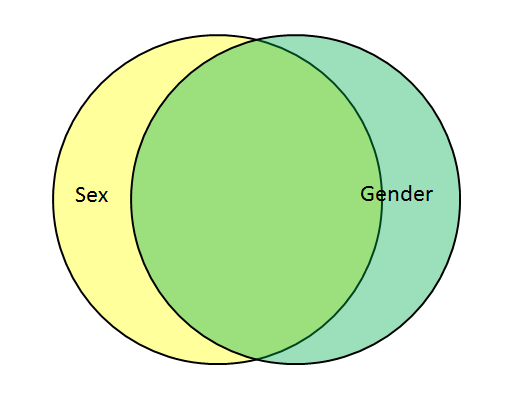

Instead humans use gender, a set of categories cultures use to classify people into groups with norms and identities, according to various factors such as appearance and interests though we are hopefully slowly realising as a society that people are best placed to decide for themselves which categories they belong in. The majority of cultures name two of these categories “male” and “female”, though it’s important to be aware that some cultures have additional categories and what these categories entail may vary between cultures.

Confusion arises because the same set of words is used to describe the biological condition of having large or small gametes and being part of a particular cultural group. Although statistically the majority of humans who produce large gametes do appear to identify with the cultural grouping “female”, and the majority of humans who produce small gametes with the cultural grouping “male”, they are distinct concepts and the overlap is not absolute. You cannot predict whether someone will fall into one category by knowing the other.

There are lots of words that are used differently in everyday speech and in scientific language. In day-to-day language, the word “significant” is just a synonym for important but in scientific terminology it has a specific statistical meaning; the probability that an observed effect is truly due to a hypothesis rather than having arisen by chance. In everyday speech “organic” means foods marketed as more sustainable, but historically it was a chemical term for covalently bonded carbon compounds. Some plants can be said to be male or female, as we will see, but that is down to the type of gametes they produce: they can have a biological sex but they cannot have a gender because they don’t have a culture that creates these roles.

As an aside it is interesting to note how the conflation of gender and sex allows stereotypes about one to influence ideas about the other. Note how the “female” peppers in the original meme are said to be sweeter and more full of seeds – their most significant properties are apparently their ability to please and their abilities to reproduce.

Another word used slightly differently in scientific and everyday language is fruit. You may not want to put them in a fruit salad, but botanically speaking peppers are a fruit, a tissue that develops from a flower’s ovaries and contains its seeds. Fruits can have many fascinating properties that are of evolutionary benefit to the plant, like a tough rind to protect the seeds or bright colours and delicious tastes that encourage gullible animals such as ourselves to disperse and even propagate them, but what they don’t have is gametes. They therefore can’t be said to have a sex, and as explained above the concept of gender is not applicable to plants.

But hold on I hear you ask, if they come from ovaries, and ovaries contain female gametes, doesn’t that make them female? Leaving aside that if this were the case all peppers would be female, as they all develop from ovaries, there are indeed circumstances under which plants and plant parts can have different sexes.

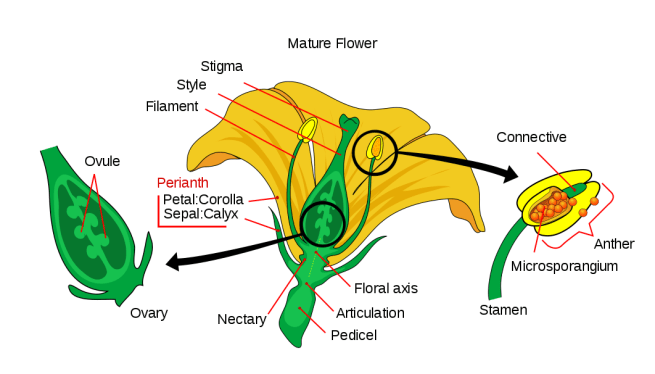

Plants are diverse, complex and fascinating and the same can be said for their reproductive strategies. For simplicity’s sake I’m going to focus on the flowering plants here, as this is the group that bell peppers (Capsicum annuum) belongs to and they are usually what people think of first when they think of a plant. Rather neatly the botanical term for flowering plants, Angiosperms, also means a plant that produces fruit.

A more in depth discussion of plant reproduction can be found here, but for simplicity’s sake, the parts of a flower that give rise to the larger gametes can be thought of as female and the ones that give rise to the smaller gametes can be thought of as male. The larger gametes are resource intensive to produce and a small number of them are sheltered in the ovary at the heart of the plant. When fertilised they will form the seeds, and the ovary will develop into the fruit around them.

The stamens can be thought of as the male parts of the flower, the structures which give rise to small, mobile gametes. Because they are so small the plant needs to spend far fewer resources on them than it does on the female gametes so can afford to be profligate with them, dispersing millions of them from the anthers at the stamen tips in pollen which is carried on the wind or by pollinating animals, hopefully to another flower of the same species. Once it lands on the sticky stigma of the other flower the male gametes emerge from the microsporangia and travel down the style to the female gametes waiting in the ovules.

Like all organisms, flowering plants want to avoid inbreeding, which could allow the expression of harmful gene variants if there is no different variant in the genome to compensate for them. Having the male and female gametes so close together might therefore present a problem, by making it too easy for a flower to fertilise itself. Different flowering plants get around this problem in different ways – they might have both male and female parts in the same flower, in which case the flower is referred to as “bisexual” (another word to watch out for that’s used differently in a day-to-day context) or “perfect”, but have different parts mature at different times. Having the stigma mature only after the pollen had all been dispersed for example make self fertilisation impossible. Alternatively the different sexes could be divided between flowers, with one type of flower producing only male gametes and another type producing only female. These flowers with only one type of reproductive parts in are called “unisexual” or “imperfect”. One plant may produce both male and female flowers, in which case it is described as “monoecious”, or if some individuals in a species produce female flowers and others produce male flowers the plants themselves can be thought of as having separate sexes and the species is described as “dioecious”.

The point of this brief detour into x-rated plant-on-plant activity? Bell peppers have perfect flowers. Even if it were somehow possible for a fruit to emerge from a male flower, all pepper flowers are both male and female, so all the other ridiculousness of this meme aside you couldn’t have male and female peppers.

Incidentally this image sent me tumbling down an internet rabbit hole to try and figure out whether anyone knew why peppers were divided into lobes. They don’t seem to, but we do know that lobe number is an inherited characteristic (and, incidentally, has nothing to do with pepper sweetness).

So why does this matter? Why have I spent a couple of hours of my life recapping Botany 101 in response to a ridiculous picture of salad vegetables? It matters because we’re living in a “post truth” era, when it’s becoming increasingly apparent that ideologically-motivated falsehoods shared on social media by fake accounts can influence the popular mood and even the composition of our governments. We all, collectively, need to get a lot better at verifying the sources and accuracy of the information we share and making sure misinformation doesn’t spread, whether it’s nonsense facts about peppers or propaganda with political consequences.

Please at the very least, before sharing memes like this on social media that purport to be informative, check whether they have included any sources for the information in the petty little infographic. Anyone with the most basic image editing software can make a nice picture, that doesn’t mean the information in it is true. Sources that would at least be encouraging to find include academic journals or news organisations reputable enough to cite their own sources, but even these shouldn’t be accepted uncritically. We all get excited by new information, and are particularly keen on it if it slots neatly into our existing ideas of how the world works, but as we get more and more of our information from social media we need to be a lot more discriminating about what we share.

If you’ll excuse a brief lapse into melodrama, today it’s peppers, tomorrow it’s people.

Oooh, didn’t know you had a blog! And now I’ve spent ages reading about gametes when I ought to be asleeeeeep… But at least now I know *why* the pepper meme is wrong (obv I knew that it *was*).

Never post a “fact” without checking on Snopes, folk. Or just ask Jules 😉

PS My fruit trees are self pollinating (both apple and blueberry).

LikeLiked by 1 person