Who had “Elon Musk buys Twitter and destroys it” on their apocalypse bingo card then? In the two short weeks since he bought Twitter he seems to have managed to sack half its staff, wreck its account verification system and hence its revenue stream by destroying advertisers’ confidence that they won’t be impersonated, make worrying noises about freedom of speech likely to translate into hate speech and lose at least a million accounts. I’m currently managing my workplace Twitter account and scheduling tweets to promote future seminars, which is rather a surreal experience as I’m not entirely sure Twitter will still be there when our December seminar takes place, or if it still is whether anyone will still be there, or whether I’ll be promoting things to a bunch of white supremacists and conspiracy nuts.

Those of you not on Twitter, or on social media in general, may be wondering why any of this matters. Unfortunately it matters because an increasing amount of the information we receive, the ideas we share and the conversations we have as a society take place through social media. While it was initially hoped that this would lead to a democratisation of discourse, in practice we have instead replaced unaccountable news corporations with other, different, but equally unaccountable corporations. Social media behemoths beholden only to their shareholders now hold our main channel of conversation hostage, ensuring that what gets the promoted is what generates the most clicks and hence the most advertising revenue. Sadly it seems that this is mostly outrage, controversy and division. Whose voices are loudest in this space, and whose are silenced by the amplification of existing marginalisations and hatred, is a decision social network users have no control over. We are the product not the community, our interests, conversation and attention sold for profit to those who hope to use our data to encourage us to consume more of their product. It doesn’t matter to these corporations whether information shared on these platforms is useful or harmful, what matters is that it’s profitable and so we see the proliferation of inflammatory hate speech, misinformation and conspiracy.

So where are these million former Twitter account holders going as the site collapses? Some of them may be abandoning microblogging altogether, but it seems that a significant chunk of them are going to Mastodon.

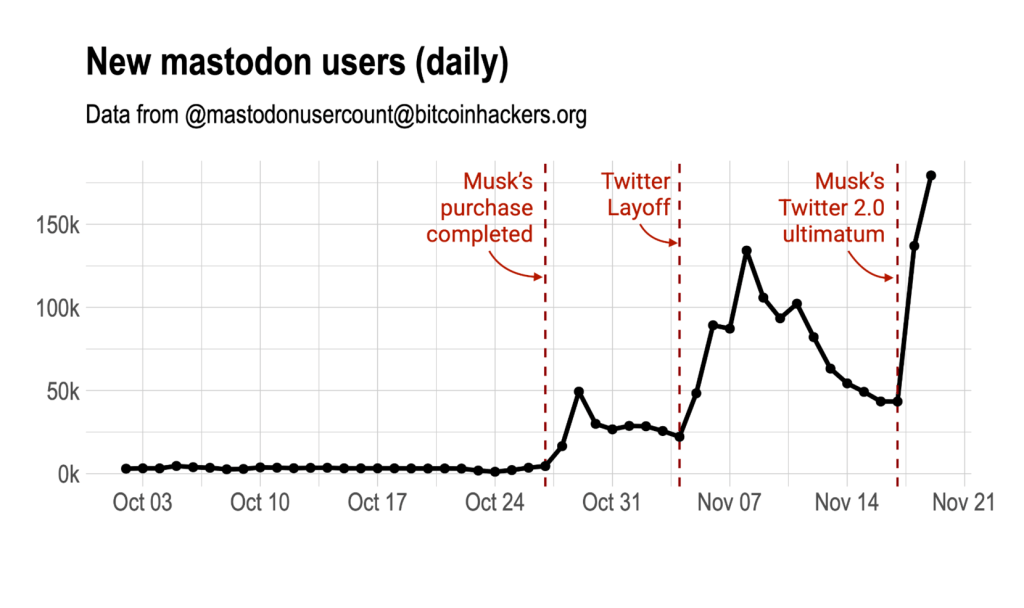

It can be seen that until Musk’s purchase was completed, the daily new users were about one thousand.

It jumped to twenty-five thousand during the first migration to Mastodon, just after the Musk’s purchase of Twitter was completed on October 27.

A second jump to 100k new users per day happened in the second wave, just after the massive layoffs in Twitter on Nov 4th.

Finally the third jump to almost 150k per day happened after Musk’s Twitter 2.0 ultimatum on Nov 17th. From a post by Esteban Moro

What is Mastodon?

Mastodon is a federated social network – unlike Twitter or Facebook say, which is run by one company, it’s easiest to think of Mastodon as a tool like email. There are a number of different servers or “instances” where your data (your account details, the contents of your posts, the timestamps of your activity, the cute picture you took of your cat fighting your slippers) are stored, there are a number of different apps or clients you can use to access these data the same way you could access the same email account through Apple mail on your iPhone or Outlook on your work PC or Gmail on an Android phone, and Mastodon is the set of instructions that allows them all to talk to one another. The great advantage of Mastodon over the traditional social networks is this decentralisation – no one owns the network because anyone can set up their own server, host accounts on it and set their own moderation rules, and the code that allows them to communicate is open source which means that no one can sell it, anyone can view it and make sure it’s not doing anything dodgy and anyone can make improvements which can be adopted if the people running it think they’re helpful. The disadvantage of Mastodon over conventional centralised networks is, well, the above – it’s great if you’re the sort of nerd who loves this stuff (cough, cough) but if you just want to use it without having to worry about how it works it’s a bit complicated and there are a lot of choices to make about which server to join and which app to use. I’ll offer some suggestions to help with this in the next section.

Mastodon is so named because, in the words of its creator Eugen Rochko: “I called it Mastodon because I’m not good at naming things. I just chose whatever came to my mind at the time. There was obviously no ambition of going big with it at the time.” and I’m sure anyone who has just mashed the keyboard to name a file because having created it you have no more menatl energy left to name it. Mastodons themselves incidentally are so called because the 19th century naturalist who named them, Georges Cuvier, thought their molars looked like they had nipples on and so named them “breast tooth”. A small prize for anyone who isn’t a sex-starved Victorian who could find table legs sexual who can explain to me how mastodon teeth look like breasts.

So how do I use it?

Just as when you want to create an new email account you first have to choose whether to go with gmail, protonmail, outlook etc, the first step of creating a new Mastodon account is to choose a server to host it on. There is a list of servers on the official Mastodon website that allows you to pick a server by topic, but currently the available choice of topics is:

- General

- Regional

- Technology

- Activism

- LGBTQ+

- Gaming

- Journalism

- Music

- Food

- Art

- Furry

Which is all very well but doesn’t quite encompass the entire breadth and diversity of the human experience. There is a slightly more comprehensive list of servers here, that allows you to search on various variables like size and language, but again it’s not terribly user friendly. In all cases before joining a server you should click through to their landing page and learn about their rules and moderation policies. This is an example of the sort of information you might want to evaluate to decide whether a server is a good fit, from toot.bike a cycling server. As more people join Mastodon I have no doubt that soon someone will build a dating app-style server match making tool that will allow you to easily and quickly find a queer poly pagan server funded through Patreon, run on renewable energy and using its waste heat for hydroponic growing, with a four-strong admin team moderating in English, French and Mandinka with an uptime of greater than 96% and a zero tolerance policy on antivaxxers, but for the moment it is rather a case of rolling the dice.

Some servers allow you to create an account straight away, other require you to apply and join a queue to allow them to manage the growth of new users and only allow new accounts once they have the capacity to handle them.

At present what the majority of new mastodon users seem to be doing is joining the original instance, mastodon.social, looking around for a while and then moving to a more specific server when they find one that’s a better fit for their interests. While this is probably the simplest way to do it there are a few things to be aware of: firstly that moving servers may be a relatively complex process, and secondly that at the time of writing there were 246K active users on mastodon.social with more joining every time Elon Musk does something bizarre. The admin team are struggling to keep up with this sudden influx so speeds may be low with pictures and new posts taking a long time to load and more importantly with the moderation team struggling to scale with the increase in users so moderation decisions may be slow or inconsistent. If you do plan to join a “starter server” then find a more permanent home I’d recommend choosing one of the other recommended ones instead.

There is a list of Mastodon apps available here, including the official apps for android and IOS. As all the code is open source, anyone can build a Mastodon app and many different independent apps have sprung up offering different features and functions. General consensus seems to be that Tusky is the best. You can also use Mastodon in your browser.

There is a quick start guide to using Mastodon here, and a more in depth guide here along with some background. Anyone familiar with Twitter shouldn’t have too much trouble getting started but there are a few significant differences you should be aware of. You have a finer degree of control over the visibility of your posts than you do on other platforms, with options to:

- Make them visible to everyone and appear on the public feed.

- Make them visible to everyone, but only if they open the thread in which they appear.

- Make them visible only to your followers.

- Make them visible only to the people tagged in the post.

Confusingly different apps will call these options different things, but generally 1 is called public, 2 is called unlisted and 3 is called private. Even more confusingly some apps call 4 direct messages, but strictly speaking they aren’t – anyone tagged in the post will see it, which could lead to awkward situations if people aren’t aware of this. If you are messaging a server admin asking them to block a user and tag that user in they will see it for example.

Mastodon also offers a content warning system and some tools for accessibility which I’ll explain in more details in the “Inclusivity and intersectionality” section below.

A slightly simpler way of joining

At the risk of sounding like a complete hipster, I joined first joined Mastodon before it was famous back in 2019 which isn’t nearly as long ago as the time distorting effects of the pandemic make it feel. I stuck around for a few months but then left because most of the people I wanted to talk to weren’t there and those who were didn’t talk much, presumably because the people they wanted to talk to weren’t there either. This time feels very different.

I signed up to a package of a server and app called Librem Social as part of a bundle of services including a messenger and a VPN called Librem One. This is offered by Purism, a Social Purpose Corporation with a focus on data privacy and autonomy. If you’re only interested in using the social network app built on Mastodon this is available on the free tier. The advantage of doing it this way is you get a stable app and an account on a well maintained server which can scale with its users supported by a trustworthy organisation with a sustainable revenue stream (or at least it seemed to be back when I first signed up anyway, before it bungled shipping a crowdfunded phone).

The disadvantage is that you miss out on the DIY, community aspect and the ability to shape the culture of your server. The risk of this is that without much feedback on the server culture, if other Librem One users behave badly the server may end up defederated by the rest of the network. Mastodon’s decentralised nature allows the admins of any individual server to block any other server, meaning that their users can’t see anything posted on this server and vice versa. Mass blocking by a number of servers means a server is effectively severed from the rest of the network, and is called defederation. This is a powerful tool to prevent the network being taken over by trolls, spammers and bigots and is a way of keeping instances accountable and self policing. It can cause problems for legitimate users on large servers who don’t have much control over admin policies however: there was some controversy when it was recently used against a large server that a number of journalists had joined after leaving Twitter when admins there refused to clamp down on transphobia by some members and harvesting and broadcasting of other people’s posts without consent. While Librem One does have a code of conduct there doesn’t seem to be as much scope for member input as with most other instances, so I do have a backup instance in mind to move to if other Librem One users start misbehaving.

Security

Mastodon does force you to consider who has access to your data in a bit more detail than with centralised social media, as you have to consider that potentially both your server administrator and the creator of your app could have access to the contents of your posts. The other side of the coin of course is that with Twitter or Facebook, while only one easily identifiable corporation has access to your data, you have no idea what they’re doing with it or who they’re selling it to. Ensure any instances and apps you choose have transparent privacy policies and if you intend to send nudes (consensually!), foment revolution or call any autocratic dictators great big smelly poo heads maybe stick to doing it via an encrypted messenger app like Telegram or Signal.

The standard online security measures apply; use a strong password that isn’t reused anywhere else, enable two factor authentication if you can, watch out for phishing scams. The latter will, I suspect, be a big problem with Mastodon; not only is it a problem likely to crop up when a large number of people are getting used to a new system and don’t yet fully understand how it works or where they can be expected to enter their passwords, its decentralised nature means there is no one easily recognised url or email address that official communications will come from. Something I personally have found a little confusing when using Mastodon in my browser is that you are prompted to enter your username when trying to follow someone on another server, to redirect you back to your home server from which you can send a follow request. While you are never prompted for your password I could see this being a design feature that would be very easy to exploit to catch new users out.

Inclusivity and intersectionality

It’s no exaggeration to say that I’ve learned more about communicating for accessibility in a week on Mastodon than I have in years of work accessibility courses. I’ve compiled the best advice from a number of posts below:

- Use image descriptions, so that blind users using screen readers can have the descriptions read out to them, and make sure that the text actually describes the image rather than providing some additional content to information in the image like the punchline of a joke for example (sorry XKCD) . There’s an excellent guide to writing informative descriptions here. Unlike many other platforms where you often have to really hunt around to find an option to add descriptions, Mastodon has an edit button that appears when you upload an image gives you a prompt to describe image for the visually impaired, and the option to automatically detect and transcribe text in the image. There is also a helpful bot you can follow that will notify you when you upload an image and forget to add a description.

- Use #CamelCase in hashtags. Capitalising the first letter of each word not only makes then easier to read than all lower case, but lets screen readers know where to break up words when reading them out.

- Use punctuation such as full stops to let screen readers know when to end sentences, and spell things correctly. Avoid weird fonts like Zalgo text that are hard to read for people with low vision. Avoid replacing letters with apostrophes or numbers. This is often done on other social networks either to avoid censorship, for example a gynaecological educator using “v*g1na” instead of the banned word vagina, or to avoid attracting unwanted attention, for example lesbians using “le5b1an” to avoid creeps searching for the word. This is unnecessary on Mastodon, which doesn’t ban any words but allows individual users to filter out anything they don’t want to see, and Mastodon deliberately disallows searches on words other than hashtags to prevent harassment.

- Moderate your use of emojis, as many screen readers read out the name of the emoji each time it appears and hearing “Grinning Face with Smiling Eyes” repeated eight times wastes a lot of time. Wordle results are apparently a big issue for screen reader users, who just hear twenty five descriptions of squares read out. If you want to share Wordle results it’s recommended to put them behind a content warning or content wrapper, which as well as flagging sensitive content can be used like a short post summary that people can choose expand if they’re interested or skip over if they’re not.

Content warnings allow discussion of potentially sensitive topics to be hidden behind a link in a post, rather than displayed by default, allowing viewers a choice of what they decide to engage with on their feeds. While there are no fast rules across the network about what merits a content warning, the broad consensus is that they should be used for traumatic subjects such as violence or abuse, anything not safe for work such as sexual content and often for “common phobias” although the definition of common is also a matter of debate. They can also be used simply as a title and are sometimes described as content wrappers when used as such) to allow people to skip over spoilers, niche content like Wordle results or long technical posts that may not be of general interest to your followers.

The use of content warnings on Mastodon has become a subject of some controversy lately with the influx of new people from Twitter, with a number of Black people but particularly Black women discussing their own experiences of racism being told (often by white people) to put their posts behind content warnings. They countered that the people who wouldn’t want to read about racism were exactly the people who needed to do so, and were broadly told that they didn’t understand Mastodon’s culture rather than having people engage with the contents of the posts. Dr Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, a Black theoretical physicist, then amplified this issue and received some honestly pretty dreadful responses from a wide variety of users across Mastodon, a combination of whitesplaining and mansplaining assuming she didn’t understand the federated nature of Mastodon, tone policing telling her not to cause negativity, victim blaming and positioning her, and Black people in general, as the problem and suggesting they go and start their own servers instead.

This issue gets to the heart of the debate over whether tools such as social media networks are value-neutral and it’s how you use them that matters, or whether the design of tools shapes the way they are used. Mastodon’s creator Eugen Rochko made some deliberate decisions to design Mastodon in a way he would promote a particular culture:

I’ve made a deliberate choice against a quoting feature because it inevitably adds toxicity to people’s behaviours. You are tempted to quote when you should be replying, and so you speak at your audience instead of with the person you are talking to. It becomes performative. Even when doing it for “good” like ridiculing awful comments, you are giving awful comments more eyeballs that way. No quote toots.

Mastodon founder Eugen Rochko

The opposing argument is that the ability to quote particularly egregious posts serves a form of community justice for marginalised groups, particularly Black people and other POC, who are unlikely to have their concerns taken seriously through official moderation channels. Quoting a post allows a legion of allies to bombard the quoted post with replies, which is likely to at least get the poster to delete the offending post and often to delete their whole account. The suggestion that people should instead be talking directly to the creator of the post, rather than to their own audience, does come across as a little insensitive, encouraging marginalised people to do the work of educating someone who is very unlikely to engage with them in good faith anyway rather than simply ejecting bigots from the space.

Personally I know which sort of culture I prefer to engage with, having found the constant anger of Twitter dispiriting and exhausting, but I suspect that this is because as a white person I didn’t need these community justice measures. As white people I think we need to do some serious self interrogation about the prioritising of our comfort on social media by creating an environment free of “toxicity” over the comfort of people whose concerns are not officially recognised and need to use these measures to stay safe. For me a calm, non-confrontational timeline feels pleasant, but I worry that we’re not talking about Bruno, prioritising avoiding conflict over resolving conflict over issues that genuinely need to be addressed. While I don’t think that a system of call outs and pile ons is a culture we should be aiming for, for a start because they can just as easily be turned on the very people who need them, we have to recognise that this culture was created by people who didn’t have a better alternative to protect themselves. We need to be creating an actively antiracist online space where concerns are taken seriously and acted upon so people don’t have to take matters into their own hands, because they’re already participating in every level of the organisation of the space and have better alternatives.

Having cautioned against tone policing I’m now going to contradict myself utterly and tone police everyone by issuing a plea to please stop calling everyone fleeing Twitter for Mastodon “refugees” – it’s a bit tasteless to compare changing social media sites to fleeing war and political persecution, and feels particularly thoughtless in the UK at the moment given the horrific conditions revealed at the Manston refugee camp and the number of people drowning in the channel.

I do wonder whether the reason Mastodon seems to be so white, and hence reflect the priorities of white users, is the same reason the conservation sector is; that it’s primarily run by volunteers, and marginalised people tend to have fewer financial resources and less time that isn’t simply spent on survival to allow them to volunteer in. The solution in the conservation sector being increasing recognised as that while we live under capitalism we need to pay people for their time if we want to benefit from the experiences, expertise and viewpoints of people who wouldn’t otherwise be able to contribute. One of Mastodon’s major selling points is that it doesn’t monetise its users’ data to sell adverts, but that means it doesn’t have advertising as a revenue stream and so servers are mostly funded by Patreon donations. It will be very interesting to see how Mastodon evolves in the future and whether there’s scope to introduce funding for admin teams without destroying what makes it special in the first place.

The future certainly looks very exciting for Mastodon and I’m extremely curious to see what it looks like in a year’s time. With Twitter’s collapse this may be the tipping point at which decentralised networks become mainstream. Tumblr and Flickr are talking about implementing ActivityPub, the protocol that makes federated networks possible, and WordPress already offers an ActivityPub plugin (sadly only on the paid plan). It can’t be denied that compared to some of the slick corporate websites and applications we’re used to, Mastodon isn’t currently the most user friendly experience and this can be as much of a barrier to access as racist culture or ableist design can. The great advantage of open source software though is that anyone can improve on it, and as Mastodon attracts ever more users and generates more buzz more people will start working to improve it.

If we come, they will build it.