This year for my five year old niece’s birthday I bought a lovely book by the ethnobotanist Anna Lewington, about a little boy who lives in the Amazon rainforest and the plants that form the framework of his daily life. And in the time between buying it and her birthday the fires started, and I nearly decided not to give it to her because it almost seemed cruel to show an innocent child the beautiful world my generation is taking from her.

By now the whole world is aware of the devastating fires sweeping the Amazon rainforest. Although the occasional wildfire starts naturally from lightning strikes, these fires are being very deliberately set and spread in order to clear forest for agricultural and infrastructure development and threaten indigenous peoples and conservation groups with the endorsement of the Brazilian Government.

The Amazon is not only an important carbon sink in a warming world, it is an absolute treasure trove of biodiversity, home of hundreds of thousand of unique species in vast, intricate networks that once torn apart can never be stitched back together again, and numerous indigenous peoples who have lived alongside this incredible richness of life for millennia without exploiting and destroying it.

Watching in despair from the other side of the world, everything seems quite hopeless. We are such an amazing species, capable of such incredible feats of compassion, creativity and discovery, and yet we seem utterly committed to a path of utter destruction of the beautiful planet we find ourselves on, the other organisms we share it with and, ultimately, ourselves.

While I so desperately want the world to unite behind the science, to heed the overwhelming evidence of the destruction we’re causing, the only way I find I can keep going in the face of all the horror is to swerve aside from evidence into the territory of faith, that we can and must do better, because I see precious little solid proof that we will do so right now. Hope therefore becomes a deliberate choice, a mental discipline, and one that I can only keep up by living as though a better world were possible, as though my actions can make a difference. I have no proof that any of the following actions will help or at least mitigate some of the harm, but I have to believe that they will.

Eat less (or no) beef

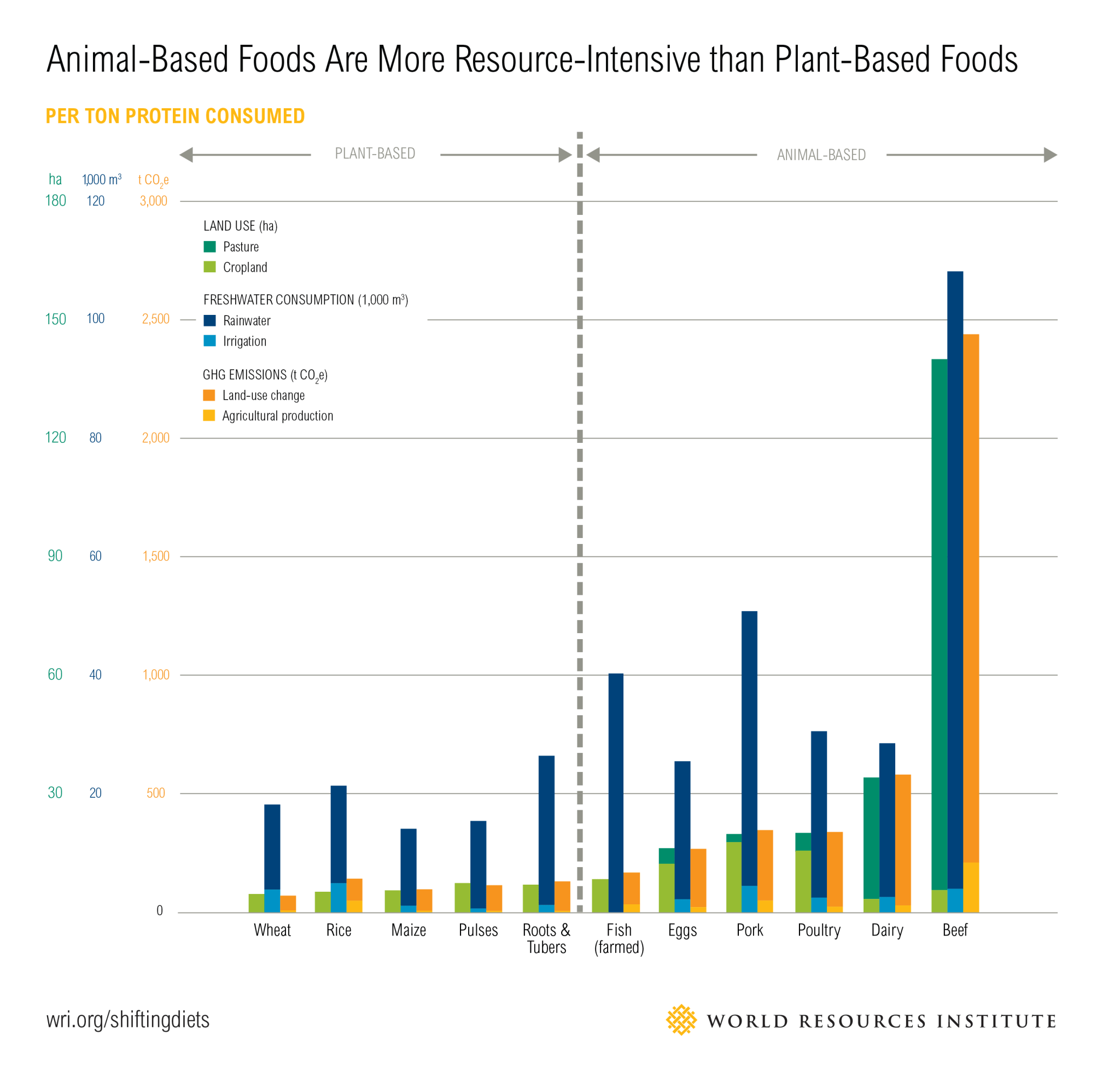

With the usual caveat that lifestyle changes for sustainability are only available to the most privileged in society, who have the resources and freedom to make choices about the way they live that others who are poorer or otherwise less privileged may not have, cutting down on the amount of animal produce we eat in general and beef in particular can reduce both our carbon footprints and contribution to deforestation.

I wish it were possible to go back in time eleven thousand years and tell the first farmers in the Fertile Crescent that cattle were actually a terrible choice of animal for domestication. Their ruminant digestive systems rely on bacterial action in the absence of oxygen to break their food down into sugars, a type of fermentation which produces methane as a byproduct. Unfortunately methane is an even more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, and we now have around a billion cattle on the planet. Unfortunately cattle therefore have a greenhouse impact even before the way they are reared is taken into consideration, and our appetite for beef means that we keep breeding more of them. But the way we choose to farm them can certainly increase their impact.

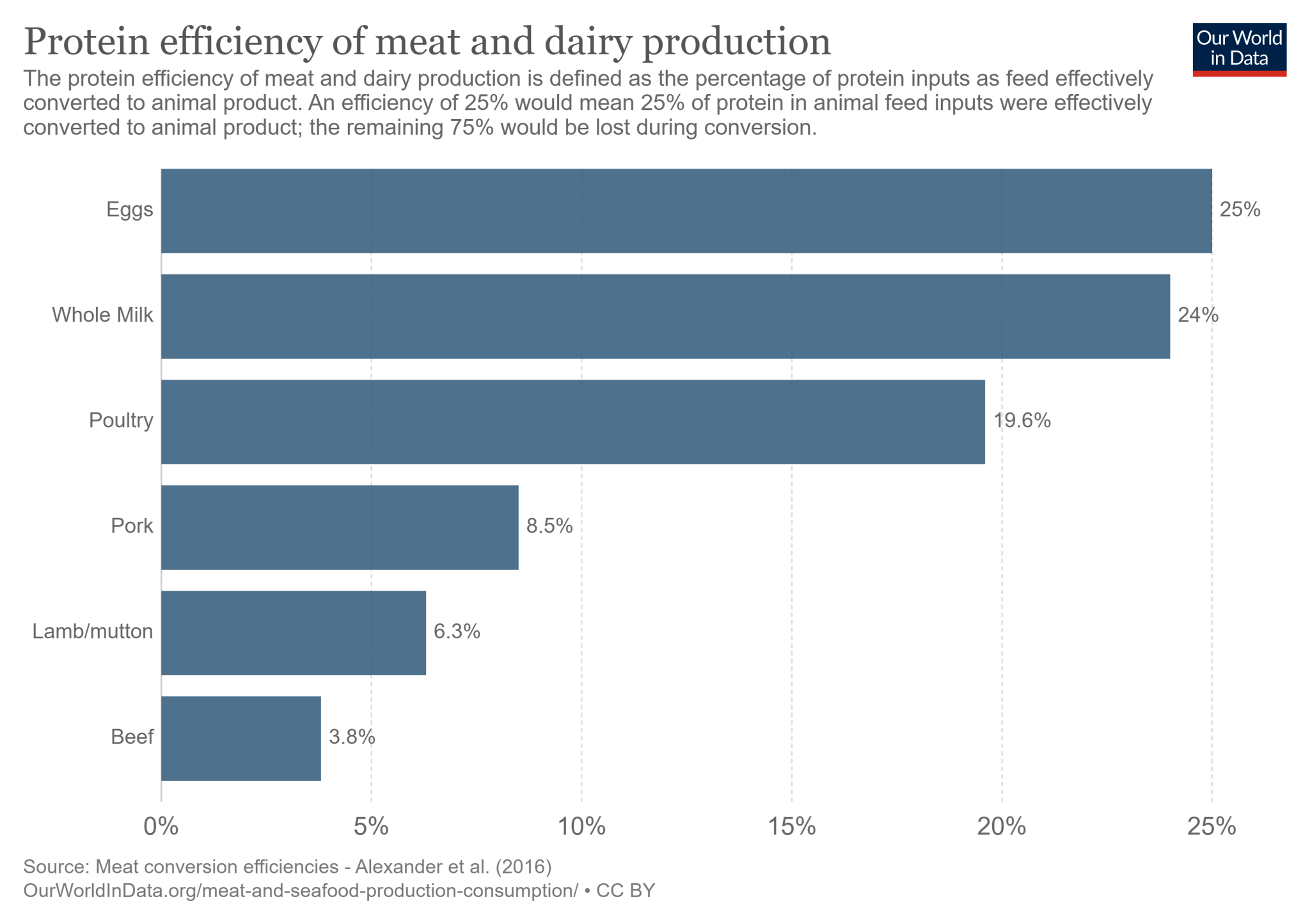

As well as clearing land to raise cattle on directly, the Amazon is also being cleared to grow soy beans, eighty five percent of which goes into animal feed. Much of this is itself fed to cattle in the Americas, which is an extremely inefficient way of getting protein into human diets – only 3.8% of the protein fed to cows is converted to protein in beef, a lower efficiency than any other meat and much less efficient than just feeding the soy protein to humans directly. Twenty five times less land would be needed to grow soy if we just cut out the middle man and ate it ourselves.

While the situation in the UK is a little different, with cows very visibly grazed in fields, what many people in the UK don’t realise is that the majority of beef cattle are “finished” or brought up to slaughter weight with supplementary feed. It has been extremely difficult to find out what this supplementary feed is composed of, and I honestly can’t say whether UK feed contains Brazilian soy or not, but it does contain grain that could be more efficiently fed to humans, protein sources that could well be soy beans, and sometimes, entirely legally, plastic.

In light of the ongoing climate emergency some institutions with large catering budgets such as Goldsmiths University and several schools have taken beef off their menus, and with the current crisis in the Amazon only making this more urgent the #0beef campaign has been launched to encourage other institutions to do the same. While it is theoretically possible to buy sustainably reared, regeneratively-grazed beef from projects such as Knepp, the reality is that this is very expensive and budget-constrained institutions such as universities, schools and hospitals will instead be buying the cheapest, most environmentally damaging meat.

As well as being raised for beef, cattle are also reared for leather on deforested land so if you buy leather goods I would urge you to contact the manufacturers first to ask whether their leather comes from Brazil.

It’s true that the remaining fifteen percent of Amazonian soy does go into making food for humans, and a common argument I’ve seen trotted out on the internet against vegetarianism is that if people stopped eating meat they’d just eat more soy. Leaving aside the fact stated above, that it’s far more efficient to feed the soy directly to humans than it is to feed it to cows, there are plenty of protein sources other than soy grown here in the UK, and Lowly Food offers a series of excellent, carbon counted vegan recipes based on local, seasonal ingredients.

It is also possible not to buy soy products from grown by deforesting the Amazon. Alpro primarily sources European soy beans and claims the remainder are not from deforested areas, Sojade uses exclusively French soy beans and Cauldron sources from China and Italy. While Marigold doesn’t state the source of their soy on their website, they were extremely helpful when I contacted them and emailed their suppliers to verify that that their soy beans didn’t come from deforested areas of Brazil, and eventually heard back from their suppliers the beans in everything but tempeh came from the US and the tempeh came Indonesia (admittedly the latter may possibly not be entirely rainforest friendly either, but I do appreciate their openness and the time the person i spoke to put into tracking down this information). If you are concerned about the provenance of your soy products, I would urge you to also email the manufacturers to make them aware that sustainable sourcing is of concern to their customers.

In conclusion, if you don’t want to give up animal products entirely I’d urge you to at least switch to less environmentally damaging meats than beef, and lobby any institutions you work for to do the same perhaps using the campaign materials supplied by #0beef. Even if you can’t give up beef entirely at least switch to eating the most sustainable beef, of traceable provenance, as a very occasional treat rather than as a weekly staple.

Help Brazilians to earn a living without harming the rainforests

It’s important to keep in mind that Brazilians are clearing rainforest for agricultural land for a reason: it will make their lives easier. More farming land means more profitable farming, which means more security and opportunities for a better life for farmers and their children. You can’t tell people to just stop doing something that is threatening the long term survival of all of humanity if stopping would prevent their own families from surviving tomorrow.

Too often calls to dismantle environmentally damaging industries such as fossil fuel extraction, industrial animal agriculture or garment production for fast fashion fail to consider the impact this would have on the workers who rely on these industries for their livelihoods. The Just Transition campaign to support US coal workers and communities to move into other employment forms an excellent model of a better way to do things. We should be doing this because it’s frankly the right thing to do, because if we claim to care about the impact of environmental destruction on humans in future it rings rather hollow if we’re indifferent to the suffering of humans now. But we also need to be doing it for the practical reason that people will resent and push back against environmental actions if they see them as something that harms them, imposed on them by a distant uncaring elite, as is so apparent with the current mood of resistance to renewable energy in the US and to “environmental red tape” in the UK.

While schemes to buy an area of rainforest and protect it from development may be well intentioned, too often they involve evicting and excluding local people from the land which simply breeds poverty and resentment. Instead I think the way forward is schemes developed by or in consultation with local people to guarantee them a better quality of life if the forest is left intact than if it is cleared, by guaranteeing a better return on forest products than what could be obtained by clearing the forest. While there are plenty of crops that flourish in intact rainforest – shade grown coffee, chocolate, rubber, sustainably harvested timber, Brazil nuts and high quality cinnamon for example – I have to confess that I’ve not managed to find any such schemes in Brazil though I have found them in other projects in Sierra Leone and Ecuador. If anyone has any information I would appreciate it.

Support indigenous peoples

The first human victims of the fires are the indigenous peoples of the Amazon, who have lived in the forest for millennia without degrading it. Bolsonaro started his presidency with a very deliberate declaration of intent not to respect the rights of indigenous people to inhabit and preserve their ancestral land, and things have become worse ever since. We need to be doing everything we can to amplify and share the voices of indigenous peoples (globally, not just in the Amazon) who are fighting to defend the lands they have inhabited for generations from destruction and exploitation, and if it’s possible financially, supporting organisations such as Survival International fighting to ensure that their voices are heard on a global stage (apart from anything else, this time of year their shop has some lovely Christmas cards).

Reduce our own carbon footprints even faster

While tragically the species and habitats being lost in the Amazon are irreplaceable, and we can no more “offset” the loss of the relationship between its species and the culture of its peoples than we could replace a dead loved one with any other random person, we can at least do something to mitigate the loss of some of its capacity to absorb carbon dioxide, by reducing the amount of greenhouse gases we produce even more urgently than we were already doing. While ultimately of course we will have the greatest impact by campaigning for change, whether that’s individual lobbying of MPs or organisations or by joining one of the many campaigning groups that are proliferating right now, I do believe there is a very strong case to be made for reducing the environmental impacts of our own lifestyles if we can.

As well as changing our diets and electricity suppliers (if we are free to do so and can afford it) and refraining from flying, we need to be urgently reducing the amount of physical “stuff” we consume and then discard. Every manufactured object that comes into our lives took energy to create and to extract and refine the raw materials that went into it, and much of this will have come from the combustion of fossil fuels. I’ve already blogged about some ways to reduce our consumption of single use items, but we need to be going further and reducing consumption in general.

We’re becoming increasingly aware of the staggering environmental impact of the fashion industry, with over 93 billion litres of water used annually to grow cotton, 1.2 billion tonnes of carbon emissions produced by the garment industry every year, 11 million tonnes of clothing sent to landfill every week in the UK, and one in three young women allegedly wearing new clothes only once or twice before disposing of them. In light of these fact the fact that t-shirts are on sale for £2, bikinis for £1 and dresses for £4 seems like madness, and that’s even before the impact of producing items for these prices on the working conditions of those making them for those prices is taken into consideration.

These facts are a very strong argument for making our clothes last longer and learning to repair them when they get damaged. There are any number of useful tutorials on Youtube on sewing, darning and replacing fastenings, and with time and practice it’s relatively easy to learn to mend things in a way that’s almost invisible, or deliberately visible as a style element. Forums and Facebook groups such as Up-Cycled Cloth Collective can be an excellent source of advice and inspiration too. Sadly however I am well aware that we live in an extremely judgmental, unequal and image-obsessed society. I as a white woman with a middle class accent am likely to be judged much less harshly in a professional environment for having slightly shabby older clothes than a person of colour with a working class accent would be for example. I’m also aware that many people who grew up in poverty and couldn’t afford new clothes are still living with the mental scars of the bullying they experienced from other children for this, and for this reason are understandably reluctant to be seen in anything less than brand new clothes now that they can afford them. As is the case with so many environmental issues, maybe we have to work on how readily our attitudes harm other humans before we can tackle how our actions harm the planet.

When you do need to buy new things, it’s less environmentally damaging to buy something that already exists secondhand than to buy something that must be newly manufactured. Oxfam has launched the #SecondhandSeptember campaign to encourage people to pledge to do just that. Clothes are probably the easiest items to source second hand, with charity shops on every high street, clothes swap events proliferating, ebay offering an option to select used items only, Oxfam offering an online shop and a number of other apps and resources available.

It’s not just clothes that are available second hand. Reconditioned electronics are available from Cex, and there are a number of online retailers of second hand books or the option to purchase used from Amazon. Books are, however, a special case where personally I feel there’s a strong argument to be made for buying new, although it has a greater environmental cost, in order to support authors and independent booksellers in a market where I am concerned that a single, vast, tax-evading retailer is something of an existential threat to the dissemination of diverse ideas. But I fear I’m not up to the challenge of finding a single metric that would allow such different threats to be weighed against one another.

Protect and improve other carbon stores

The biosphere, the Earth’s gossamer-thin skin which is so far as we know the only infinitesimal fraction of the cosmos in which life exists, is effectively a closed system. Material is not created or destroyed within it, merely converted into different forms. The water that we drink, the oxygen that we breathe, the nitrogen in the proteins that make up our bodies have only reached us after innumerable cycles through other organisms, and will continue cycling long after we’re gone. We have nowhere to extract resources from other than the Earth, we have nowhere to throw them “away” to other than this planet. Given these constraints, it quickly becomes apparent that the linear flows of material we’ve built our society around – extraction, use, disposal – are nonsensical and cannot be sustained: there is only so much we can extract, and only so many places to put it when we’ve finished using it.

One such cycle is that of carbon, the element on which all life on Earth is based. Carbon forms the backbone of the amino acid chains that make up the enzymes that carry out all the reactions of life and the structural proteins that make the bodies of animals and key parts of plants. It is also the fuel that powers all living things – the process of photosythesis uses energy from sunlight to convert water and carbon in the air in the form of carbon dioxide into oxygen and sugars. These sugars serve as a store of chemical energy which be released by transferring the carbon they contain back into carbon dioxide. Alternatively, rather than releasing their energy immediately sugars can be stored and incorporated into cellulose, the structural material that makes up plant tissues such as wood. The Earth’s carbon therefore exists in a constant state of dynamic equilibrium, some as carbon dioxide in the atmosphere or dissolved in the ocean, some in the bodies of living things or once-living things decaying in the soil.

While most of us are now aware that we are dramatically increasing the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels, the carbon residues of the bodies of living things that have been sequestered in the ground over hundreds of millions of years, fewer people are aware that we are also altering the position of the equilibrium between carbon in the atmosphere and carbon in living beings and living soil. As they grow plants use only a proportion of the sugars they create for energy, locking the rest away in the woody tissues that make up most of the structure of their bodies. It is locked away there for the duration of the organism’s life, which for undisturbed trees can be thousands or even tens of thousands of years.

When woody material dies and decays the carbon is not immediately returned to the atmosphere either, but is absorbed and cycled through a vast interwoven web of fungi, bacteria and invertebrates which hold it in rich, healthy soil. Unfortunately, living soil is distressingly easy for humans to destroy , by failing to replace the nutrients we extract from it in crops through not returning organic material to it but instead burying it in landfill or buring it in incinerators or washing it out to sea, by ploughing it up so that the microrganisms that should be storing the carbon are dessicated and burnt up by direct sunlight and by killing off the invertebrate life that should be cycling and reincorporating organic matter with pesticides. If our farming practices don’t change it is estimated that we only have sixty to one hundred harvests left in the world’s agricultural land before the soil is completely exhausted.

“Soil wants to be alive, so the question is not how to add life to the soil, but how not to destroy it”

While it feel as though we can’t do much to protect living carbon stores and threatened species in Brazil, we can at least try to protect those we have in the UK by supporting agricultural practices that don’t strip soil fertility, and by valuing and protecting our own unique ecosystems, from majestic broadleaved woodland to scrubby wild plants on roadside verges and the incredibly varied tapestry of invertebrate life they sustain – Darwin’s original tangled banks. Too often we seem to believe that nature is something that exists in distant places, filmed in loving high definition and displayed on glowing screens, when we can find smaller beings just as beautiful living out struggles just as dramatic in the patch of weeds we destroy for looking “messy” or the trees we fell for harbouring insects that drip honeydew on our shiny cars.

On a household level we can also do our bit to keep carbon in the soil by composting our food waste. Disposing of organic material – anything that was once living – in the general rubbish will result either in it being sent for incineration, in which case the carbon it contained will simply become more carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere, or in it being sent to landfill. On the face of it sending organic material to landfill may sound like a good idea, as it will rot back into the ground, but in practice there are two problems with this approach. The first is that as food waste is buried under layers of other rubbish in the landfill oxygen can’t reach it, and in the absence of oxygen organic material will be broken down by anaerobic microbes like those in the digestive systems of cows, producing methane. In 2017, the latest year for which figures are available, it was estimated that landfills in the UK emitted 563 kilotonnes of methane, although believe it or not this is actually something of a success story as in 1995 they emitted 2,524 kilotonnes – we have at least managed to reduce the amount of food waste we’re sending to landfill as a country, a trend which I hope continues. The second is that as well as food waste landfills also contain a toxic chemical stew of heavy metals, plasticisers, fire retardants, pharmaceuticals and assorted other industrial filth, rendering everything in it inhospitable or positively toxic to life. Thus marinaded in this toxic stew, the other vital cycling nutrients that food waste contains – nitrates, phosphates, potassium and other trace minerals – are rendered inaccessible and cannot go back to enrich the soil, impoverishing it further.

Composting provides an alternative. Many local councils now offer a food waste collection service for industrial composting, although the details of what is collected and how vary by region, or if you have access to some land you can compost your own and make your own nutritious growing media as a bonus. If you’re new to home composting the following video is an excellent place to start.

There are quite a few misconceptions about composting out there, the most significant of which is that there are some things which cannot be composted. To be clear, anything that grew from the Earth can be broken down and return to the Earth – there is nothing that was once living that will not eventually be broken down by microorganisms. However it is true that some things are easier to compost in some ways than others, which is where the confusion arises. Some council composting schemes do not accept cooked food or meat, not because these things will not eventually compost but because of concerns that they will attract rodents to composting sites before they do. Likewise some people choose not to put these things in their home compost heaps for the same reason. Edible oils will also eventually break down, but need to be very thoroughly mixed in with other compostable materials because dense patches of oil will coat composting animals like worms and insects that breathe through their skins, causing them to suffocate. If you add composting worms to your compost heap to help the material the material break down faster, different sources say different things about what the worms can and cannot digest – I’ve read different sources saying that you should avoid chillis, members of the allium family like onion and garlic, raw potato peeling and citrus, although personally the only one of those I’ve noticed a problem with in my own wormeries is citrus peel. But again this doesn’t mean that those items are not biodegradable, just better put on the general compost heap than in a wormery.

There is of course also a concern about composting diseased plant material, for example tomatoes and potatoes with blight, then putting the compost back on your plot and potentially spreading the disease to your next crop. While Charles Dowding very deliberately does compost diseased plant material, he has very large compost heaps that reach high enough temperatures to kill off any pathogens. If your heaps are smaller and less active than his you probably are better off sending diseased plant material off for composting on an industrial scale by the council.

Promote ecological awareness

“Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand.”

Carl Sagan

This was a difficult post to write. It took me several months to finish because I had to keep leaving it, and I have to confess that I cried several times while working on it. Some people have the gift of turning their broken hearts into art, of weaving words into something that can motivate and inspire people, while my own howls of rage and despair seem to come out as a collection of graphs and a love-letter to compost. I don’t have that gift. I don’t know how to make people understand what I see, that the incredible web of life around us is so beautiful, so fragile and so essential for our continued survival as a species. But I have to keep trying, because I don’t know what else to do, and it does seem that something is finally shifting in the conversation. Four million people in 185 countries took part in September’s Climate Strikes. 54% of people polled said that environmental issues would influence how they voted in the upcoming UK elections. And not just in my self-selecting greenie social bubble but outside it, among my work colleagues and the people I went to school with, it seems that people are becoming increasingly aware that we can’t go on the way we have been, even if no one yet quite knows what to do about it.

We need to keep having these conversations, not just reminding people of the scale of the problem but reminding them there are things we can do, not just to reduce our impact but maybe even to improve things, and we need to keep working for a more just society so everyone can be part of the struggle for a better future rather than just struggling to survive. We need to “make sure people remember that a closed system is a closed system even when you can’t see the edges.” (Becky Chambers), that our continued survival depends on the functioning of the beautiful, mind-boggling complex living planet we inhabit, but we also need to remind ourselves that there is a better future worth fighting for, and if we keep talking and keep trying then maybe we can all get there. And that’s what I want to be able to tell my nieces in the end, that I kept fighting in the face of despair and did all I could.