There has been a fair amount of alarm in sustainable living circles recently over an an investigation conducted into bamboo mugs by the respected German consumer testing organisation Stiftung Warentest, published here(pdf) and kindly translated into English by my father here. The report found that they were often misleadingly labelled as biodegradable when they are not, but of perhaps more concern is that under the testing conditions of this investigation the mugs tested leaked melamine and formaldehyde into the liquid they contained.

The issue seems to be that many consumers believe bamboo crockery to be made of pure bamboo, when it is actually composed of bamboo powder embedded in a melamine resin, commonly called simply melamine. Melamine resin has a long history of safe food use dating back to the 1940s, but has not historically been used for hot, acidic liquids such as coffee. Melamine resin is made from two toxic compounds, one that is confusingly also called melamine and formaldehyde, which react together to form an inert polymer. Although that sounds alarming, it’s worth bearing in mind that many common, harmless substances are made from harmful precursors; table salt for example is made from ions of the toxic elements sodium and chlorine.

The concern raised by the study is that while melamine tableware remains inert when used for cold food, hot, acidic liquids such as coffee may cause it to break back down into its toxic building blocks and these may seep into the coffee and be consumed. The Stiftung Warentest investigation involved filling mugs made from bamboo in melamine resin with a 3% acetic acid solution and keeping them at 70°C for two hours, repeating this seven times, and testing for the presence of melamine and formaldehyde in the solution after the third and seventh test. They found very high levels of melamine after the third refill in four of the twelve mugs tested, and in three others after the seventh refill. They also found formaldehyde in the liquid, in some cases at high levels.

So does this mean that bamboo mugs are unsafe to use? Before concluding that, I wanted to determine how accurately the test conditions that caused the mugs to shed melamine and formaldehyde (3% acetic acid at 70°C for two hours) actually replicated the condition under which a coffee mug would be used.Sadly I no longer have access to a GC mass spec, so am unable to check for the presence of melamine or formaldehye in the liquid directly, but I can test some of the assumptions made in the test: that a 3% acetic acid solution replicates the acidity of coffee, and that a beverage in a bamboo mug would stay at 70 degrees centigrade for two hours, using my ecoffee cup.

Unfortunately the article doesn’t go in to very much detail of the methods used – I wasn’t sure whether the 3% acetic acid solution used was by weight or by volume, and I’d have liked to know how they assessed the the concentration of melamine and formaldehyde. I would also have liked to know why they used the test conditions they did – why for example they used a 3% acetic acid solution instead of coffee (I presume this was to get a cleaner sample without all the compounds from the coffee in which might mask the presence of compounds from the mug on a GC trace, but it would have been nice to have had this confirmed).

The acidity of coffee

I remembered that among the many horrors lurking in the depths of my kitchen drawer was a book of indicator paper I’d acquired to test the soil at my allotment but never gotten around to using, so brewed a pot of coffee, drank most of it (the first step of all science experiments but more directly relevant here) and tested a droplet with and without soy milk.

This proved…less than illuminating, as the pH paper I had was incapable of distinguishing between pHs between 5 and 7 which is quite a substantial range. So I did what thwarted geeks do whenever they can’t work out the answer and just googled it. It seems that the pH of coffee is between 4.3 and 4.6, and that I should probably leave an unfavourable review of that indicator paper.

So how does that compare to the pH of the acetic acid solution used as a model for a beverage in the investigation? As the article didn’t specify whether the percentage was by weight or by volume, the first step was to determine the molarity of the acetic acid solution in both cases:

| 3% by weight: | 3% by volume: |

|---|---|

| 3mg acetic acid in 100ml

Therefore 30g acetic acid in 1 L As the molar mass of acetic acid is 60.052 g/mol: 30g / 60.052 g/mol = 0.499 M |

3ml acetic acid in 100ml

The density of acetic acid is 1.049 g per ml Therefore 1.049g x 30 = 31.47 g acetic acid in 1 L As the molar mass of acetic acid is 60.052 g/mol: 31.47 g / 60.052 g/mol = 0.524 M |

I was extremely relieved to discover that, for the degree of accuracy I’m working to here, the values are similar enough that I could approximate them both to a 0.5 molar solution so whether it was by weight or by volume didn’t matter.

pH is a measure of the effective H+ ion concentration in a solution. As acetic acid is a weak acid that doesn’t dissociate fully, I’ll need to use the Ka or acid dissociation constant to calculate this, using an equation I can’t rearrange here properly because you can only get the LaTeX plugin for WordPress on the paid plan apparently.

Ka acetic acid = 1.76 x 10-5 = [H+] x [CH3COO–]/ [CH3COOH]

As [H+] = [CH3COO–],

1.76 x 10-5 = [H+]2/ [CH3COOH]

Therefore [H+] = √1.76 x 10-5 x [CH3COOH]

[H+] = √1.76 x 10-5 x 0.5 M

[H+] = 2.97 x 10-3

Calculating the pH from this concentration gives

pH = -log[H+] = -log (2.97 x 10-3) = 2.53

In conclusion I never want to write out that many subscripts and superscripts manually in HTML ever again, but more importantly:

A 3% acetic acid solution has a pH of around 2.5, which is considerably more acidic than coffee which has a pH of around 4.5. I would therefore argue that it does not serve as a good proxy for coffee in this test.

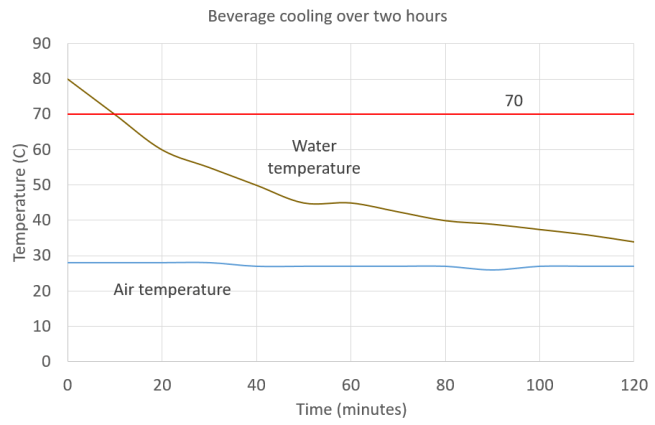

Temperature of the beverage over time

I then went on to test whether it was reasonable to assume that the beverage would remain at 70°C for two hours, by setting a timer to go off every ten minutes and irritate the shit out of my girlfriend, and measuring the temperature at these timepoints. I kept the silicone sleeve on the mug at all times and covered it with the silicone lid when not measuring the temperature but otherwise did not insulate it in any way.

The line indicating air temperature starts at a constant 28°C until 30 minutes then falls to 27°C where it remains for the duration of the experiment with one brief dip to 26°C at 90 minutes.

The first measurement of liquid temperature at time zero is 80°C. After ten minutes this has fallen to 70°C (and crosses the line marking the 70°C temperature in the original experiment) the temperature continues falling in a curve, reaching 50°C after 40 minutes, 40 °C and 34 °C at the end of the experiment after 120 minutes.

Interestingly the water I boiled started out at 80°C, which is actually higher than the 70°C used in the original Stiftung Warentest experiment. The temperature fell very rapidly however, reaching 70°C after ten minutes and continuing to cool thereafter. I presume the original investigators had to insulate their mugs very thoroughly to keep them at 70°C for two hours, which doesn’t replicate the situation that would be seen in everyday use.

It should also be noted that the usual rate of cooling in the UK would probably be even faster, as the rate of heat loss is proportional to the temperature difference across the materials and the recorded air temperatures of 26 to 28 °C are unusually high for the location. These measurements were taken in during the hottest month of one of Europe’s hottest ever summers, which is of course the reason we’re buying bamboo mugs in the first place, to try and reduce our consumption of single use materials in the hope of mitigating climate breakdown slightly. But on a more typical day with a cooler air temperature coffee in a bamboo mug would cool even faster.

It therefore seems unlikely that a solution at 70°C would not sit in these cups for two hours.

Conclusions

I should stress that I was not able to measure melamine or formaldehyde in the liquid directly, so I have no idea whether it leaches into the drink under conditions of normal use, but given my experiments it seems unlikely that the conditions used by Stiftung Warentest do in fact replicate normal use.

So given the above will I keep using my ecoffee cup? Entirely coincidentally I avoided having to make a decision by breaking it the day after carrying out these tests. By, erm, rolling down a hill and landing on it. I was entirely sober when I did this too, and I’m genuinely not sure whether that makes it better or worse. Moving on.

Would I consider buying another “bamboo” mug? No, but not because of the concerns about chemical contamination. This is actually my second ecoffee mug, I cracked the first in August 2018 dropping it on a pavement four months after buying it in April 2018. The fact that my second one lasted around a year is not terribly impressive either to be honest; the whole point of buying these mugs is ultimately to reduce my consumption of materials and energy in my day to day life, but if they’re not terribly robust they don’t do very well in that regard. Although it could be argued that they see a lot of of use – I carry a reusable mug with me at all times outside the house and use it at least three times a day . I bought a previous Thermos mug on a camping trip when I was 19, used it just as intensively, and it lasted for a decade and a half until I left it on a train. For all I know it remains unbroken to this day.

Having a broken mug to dispose of leads on rather neatly to the subject of the next part of the study: how sustainably “bamboo” mugs can be disposed of.

Sustainability of disposal

The second and perhaps more important point of concern raised by the German study is that bamboo mugs are marketed as an ecological product which can be disposed of sustainably when this is not in fact the case. While bamboo itself is a natural material which biodegrades, melamine resin does not. Many of the beakers examined in the study made the claim that they were natural, biodegradeable or recyclable, which was at best misleading and at worst false information. The ecoffee website (accessed 19/08/17) states

Recent changes to EU law mean that we are no longer able to claim our product is biodegradable. In order to meet these rules, a product must biodegrade 90% within 6 months. For all consumer durable products, this is simply not achievable.

When I first purchased the cup I believe I understood it to be biodegradeable, but I am no longer able to find information to this effect. However to their credit ecoffee are now offering a freepost return address to take back components for disposal. I would hope other manufacturers of these products will do the same.

To end this post on a cliffhanger, on the 5th of August last year when I understood my bamboo mugs to be marketed as biodegradable I buried the cracked to find out how well this would actually work. Gary of Jack Raven Bushcraft not only very kindly let me do this at the bushcraft camp but even lent me a mattock to dig with, an action that I thought demonstrated remarkable trust from a man who had just watched me set my coffee maker on fire. It weighed 101 grams when it was buried, and I hope to excavate it when I’m next in those woods on August the 25th so check back for a shockingly nerdy update to this post then!

several hot drinks are close to pH 2.5, Lipton lemon tea and peach tea are pH3 for example. If you have these drinks without milk (which would be normal) they will be close to 100C when entering the cup.Coke and many other cold drinks are also pH 2.5 and could potentially be kept in a cup for longer than 2 hours, even though they might be cold.

Yes its not a perfect replication of coffee drinking conditions, but to me it seems a fair approximation of use given the limitations of experimental conditions.

The levels of dangerous compounds were many times over the acceptable limit. It seems quite likely that these cups could certainly exceed the recommended levels of formaldehyde and melamine in some perfectly normal conditions of use. Surely the precautionary principle means we should stop using and recommending these cups, especially since there are other inert and more recyclable alternatives available – like stainless steel?

LikeLike