I love foraging for wild food, as a way of exploring new flavours, learning more about the natural world around me and deepening my connection to it. My walk to work across the university campus takes me past dandelions, nettles, ground ivy, jack-by-the-hedge, wild thyme, dead nettles, linden trees and a new discovery this summer bristly oxtongue. These foraged plants can and do provide me with tasty salads, unusual seasonings and the occasional cup of tea. What they do not provide is any appreciable quantity of protein, or in all likelihood replace the calories I expend finding them. They certainly do not keep me from going hungry in any meaningful way, and I’m a reasonably knowledgeable forager with access to a diverse, unpolluted landscape.

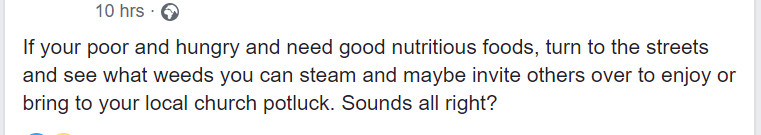

They certainly would not help someone in poverty in the way this poster in a foraging forum I frequent believes they would.

While this is the most egregious example of this idea I’ve heard expressed recently, it’s not the first time I’ve encountered it, so it’s time for another “someone is wrong on the internet” post.

It’s hard to know where to start responding to the idea that the poor can feed themselves by eating nutritious weeds from cracks in the concrete (that have probably been pissed on by dogs and coated with car exhaust fumes even if they haven’t been treated with herbicide), but for a start it isn’t elitist to say that wild plant identification is a skill that requires both time and resources to learn, and the consequences of getting things wrong can be deadly. People struggling with multiple jobs lack the former, and poor people by definition don’t have the money for books and courses. Furthermore many among the poorest in society are disabled people who might find the physical labour of foraging challenging, or immigrants who may not be familiar with the local flora leading to tragedies like this in Germany, where Syrian refugees mistook poisonous mushrooms for a harmless species they were familiar with.

Secondly and most importantly, the amount of nutrition you get from foraged foods is tiny in return for the effort you put into finding them. John Lewis-Stempel catalogues the struggles and hunger he experienced while living on foraged food for a year, in the verdant valleys below the Black Mountains in his excellent book, and some friends and I tried to walk and forage ourselves in the Kent, the “Garden of England” as an experiment which failed entirely. Wild food is not only less abundant on the streets, but if all the nation’s hungry were to take this poster’s advice it would have to be shared out among far more people.

And finally of course, if you’re poor enough to be considering eating weeds from the pavement you are unlikely to have pots to steam them in, a stove to steam them on or money to pay the energy bills to power it.

This isn’t to say that the urban environment can’t be fertile grounds for foraging: a surprising number of London street trees around Heathrow (where the orchards that used to serve the city once grew) are apples, pears or cherry plums and you can keep yourself in crumble very nicely come autumn with a picking cage on a stick, a high visibility jacket and an air of authority. 47% of London is greenspace, a decent proportion of which is publicly accessible, and John Rensten has written an excellent book on what you might find there. But the idea that these measures could make a meaningful difference to the lives of people in food poverty is laughable.

The root of the problem goes beyond foraging though: we need to get away from the attitude that poverty is due to a personal failing of intelligence or work ethic and poor people could sort themselves out if they “just” followed a few simple suggestions: foraged for some weeds, managed their money better, did some research on the internet. Poverty is a structural failing of the way our society is organised, so that in a country with enough resources to provide food and shelter and the basics of a dignified existence to all we have arranged things so that no matter how hard some people try they will never be able to access them. Jack Monroe, a highly intelligent, resourceful and articulate person, has written movingly about the struggles of poverty and the near impossibility of escaping a spiral where

the bank charges…mounted up when bills bounced, and the late payment charges, and how quickly a £6 water charge can spiral into hundreds of pounds in late fees and bank charges, and nobody will give you the smallest of overdrafts, to tide you over, because those charges and subsequent interest are worth far more to a high street bank.

In truth poverty is a spiral that anyone, however intelligent or well connected can fall into and struggle to escape from after an illness or disability, a relationship breakup or a redundancy. The idea that someone could escape by feeding themselves through foraging is a classic example of the type of victim blaming people use to make themselves feel safe; if you can convince yourself that you know the tricks you would use to get out of poverty, you can reassure yourself it would never happen to you. And if you’ve convinced yourself that there are things that can be done to avoid misfortunes like poverty from befalling you, then people who do fall into poverty and fail to extricate themselves must have something wrong with them to be failing to take these simple measure. The same thinking occurs with victims of violent crime, sexual assault and refugees forced to flee: if you tell yourself this happened to them because they did the wrong thing, and you would do the right thing, you never need worry that it would happen to you.

We need to be better than that, as foragers and as a whole community.

Sounds all right?

2 thoughts on ““Let them eat weeds”: Foraging is not a solution to food poverty”